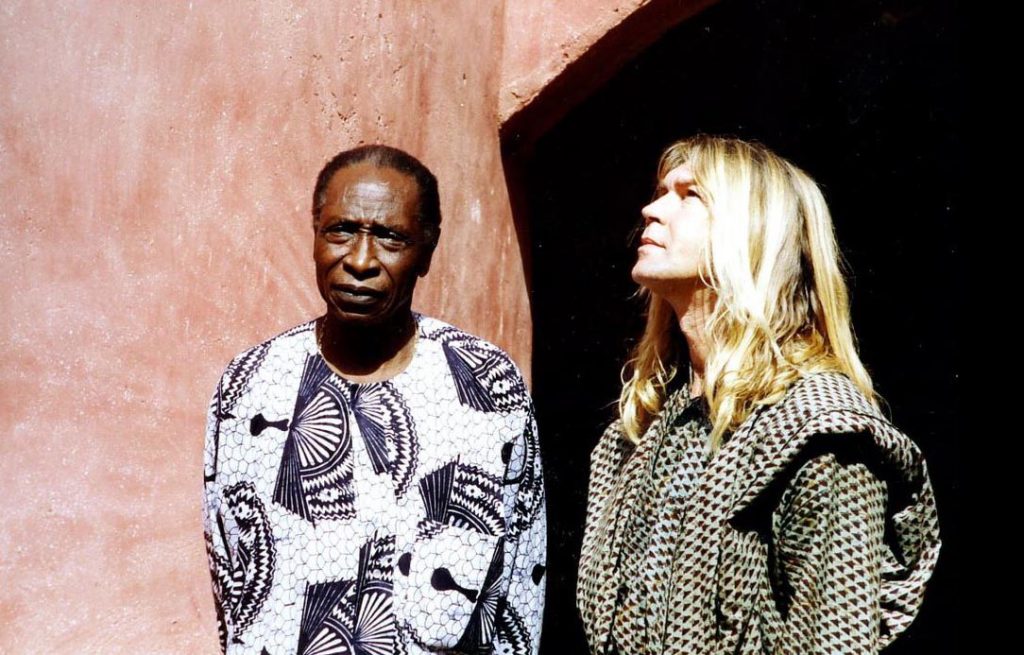

Island of Goree

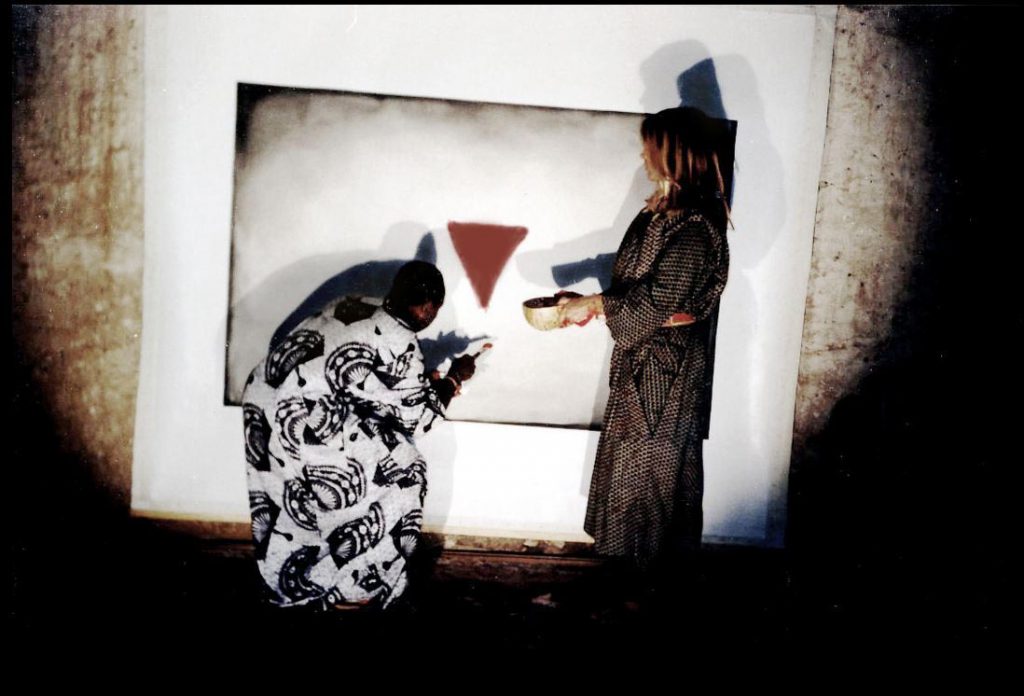

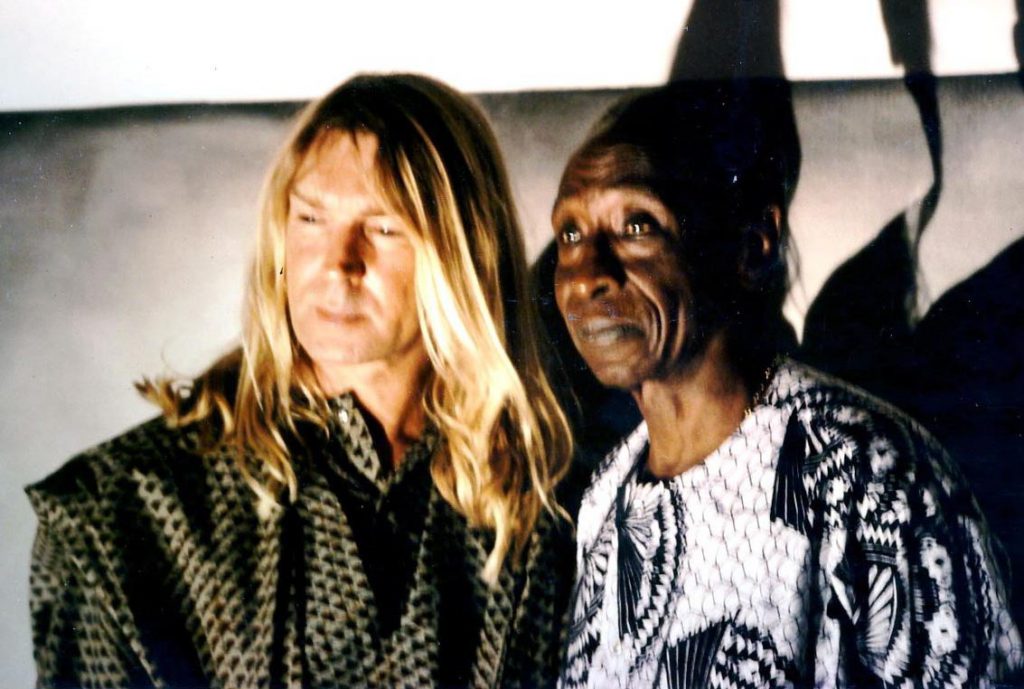

Lucas and Joseph N’Diaye, symbolising Africa’s last slave

In the basement of the House of Slaves, the departure point for tens of thousands of black men on their way to the Americas.

Sénégal,

The first biennial arts event

Just a quarter of an hour away by boat from the first biennial arts event in Dakar, Senegal, was a unique location that LUCAS has made his own: the House of Slaves on the island of Goree, which from the 17th century was the starting point of the slave trade and therefore one of the most poignant settings in Africa and indeed for the history of mankind. The event had been prepared in utmost secrecy for months and LUCAS was about to make a splash. The media and television cameras made the right decision when they chose to desert the officials thronging in the capital that day.

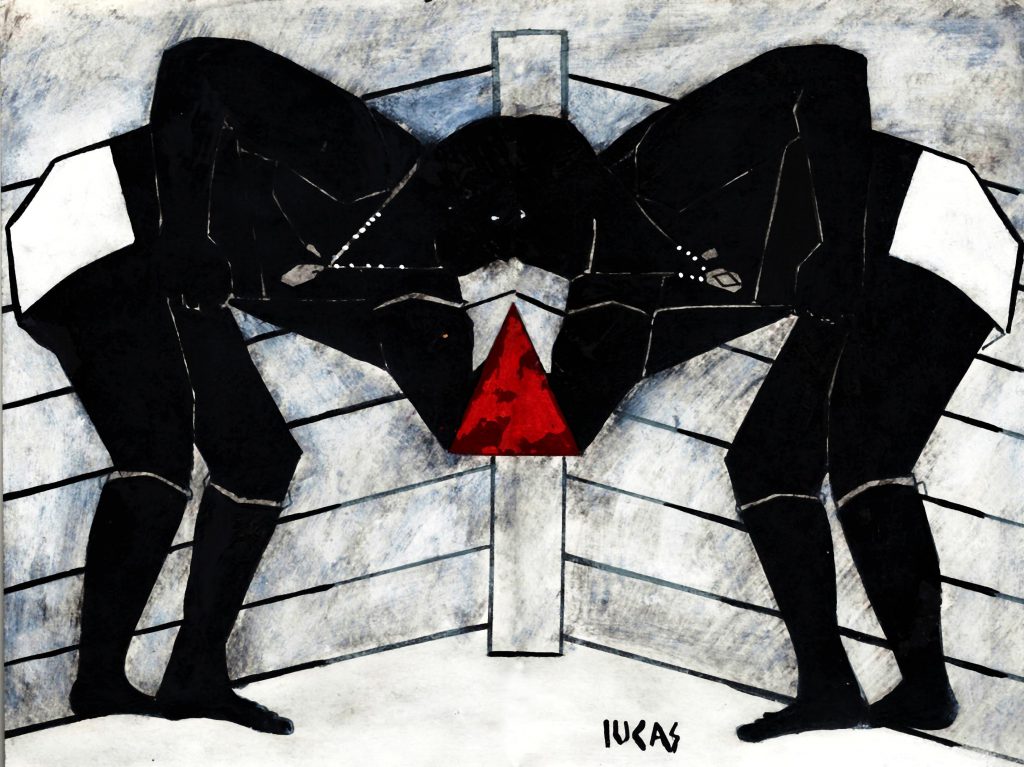

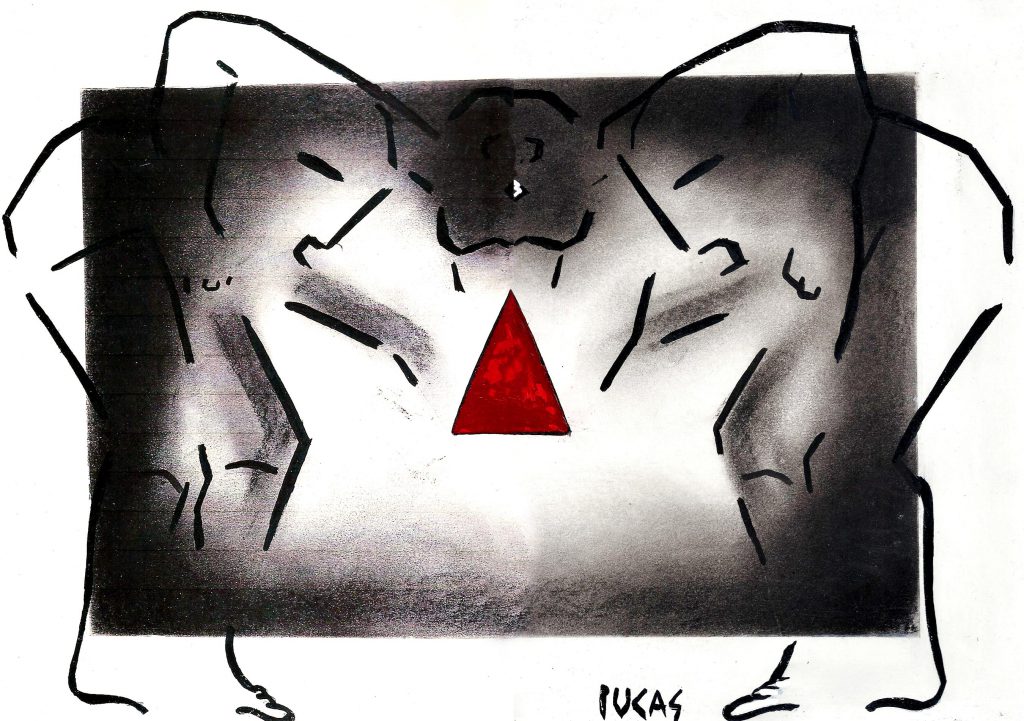

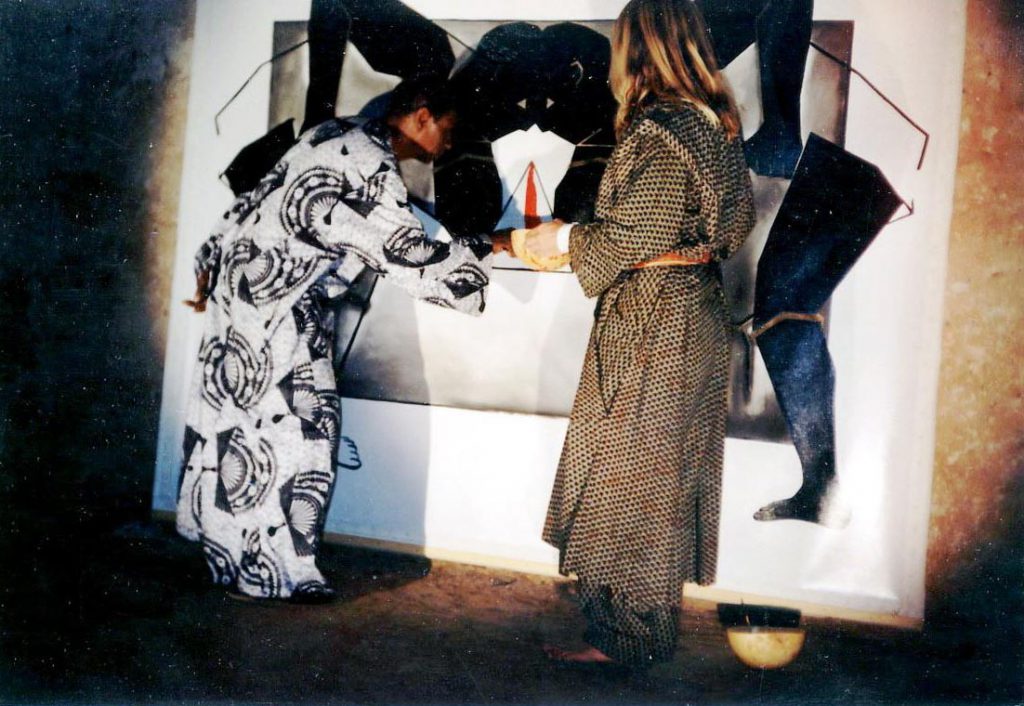

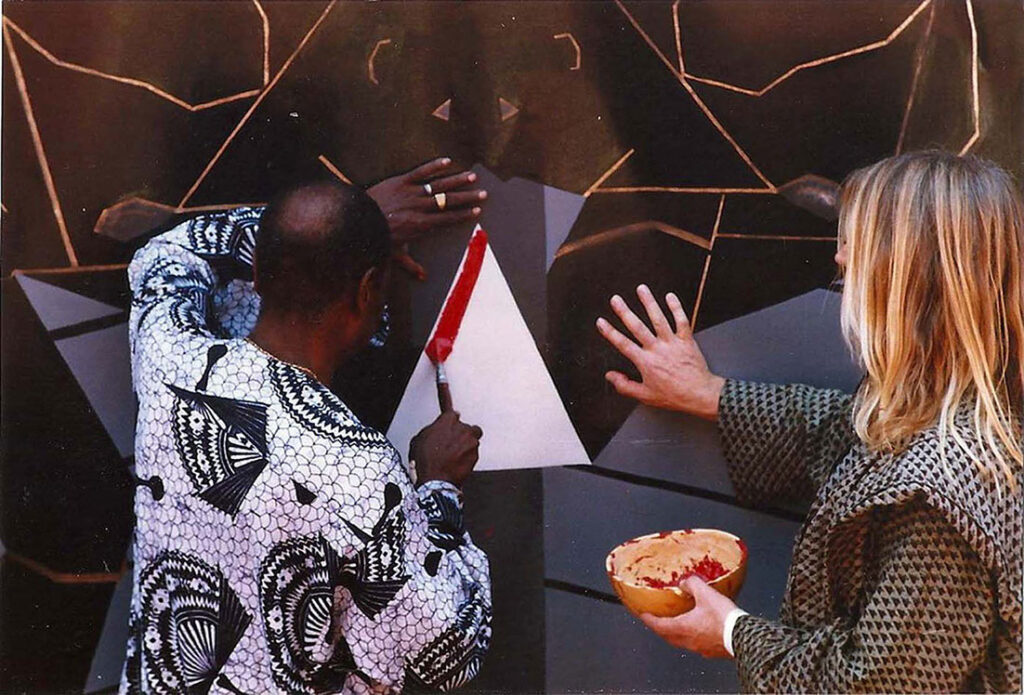

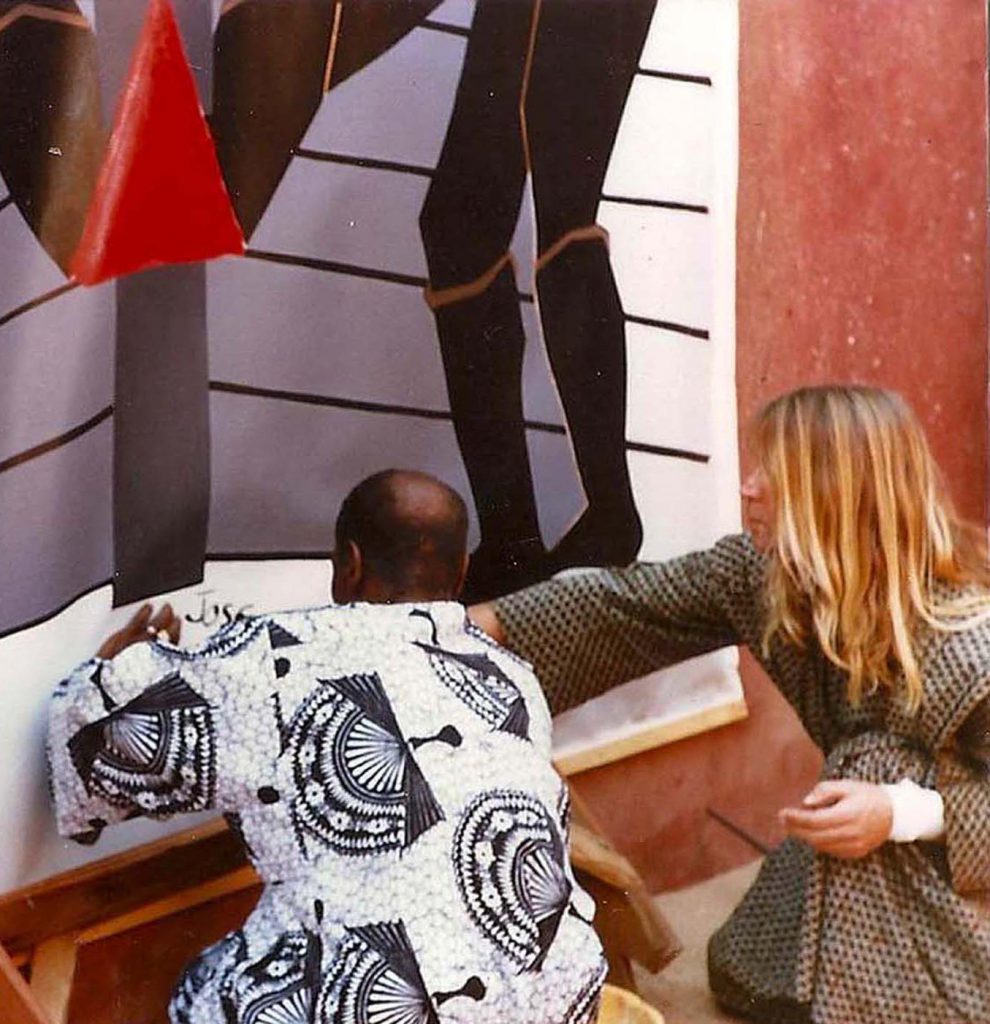

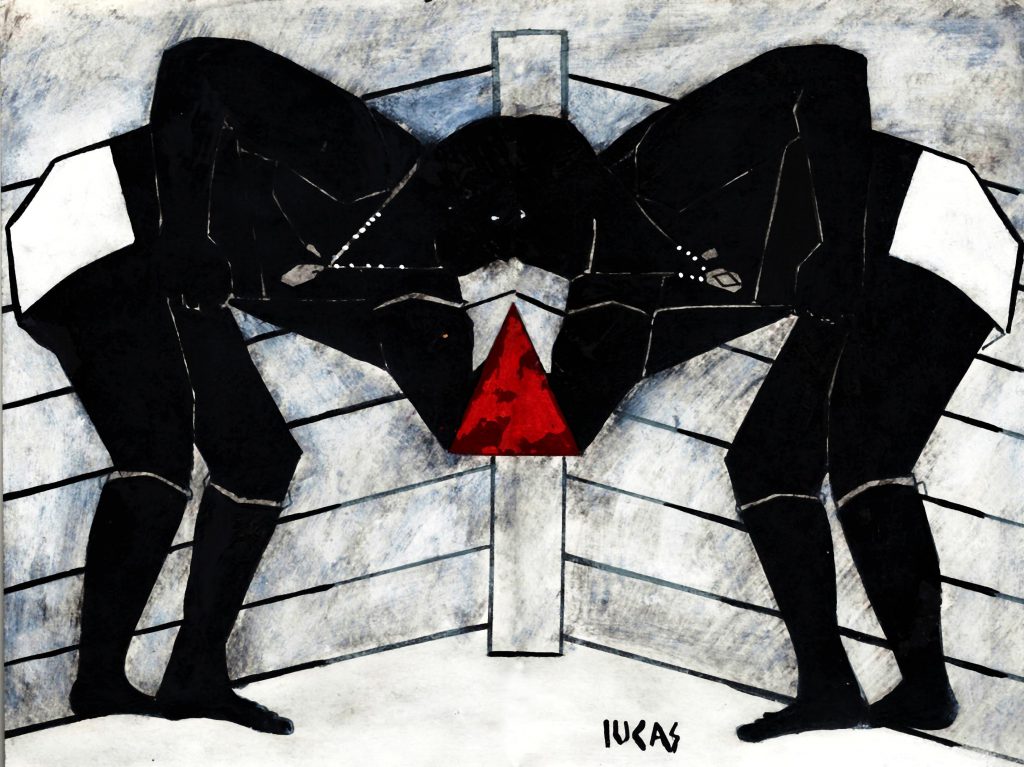

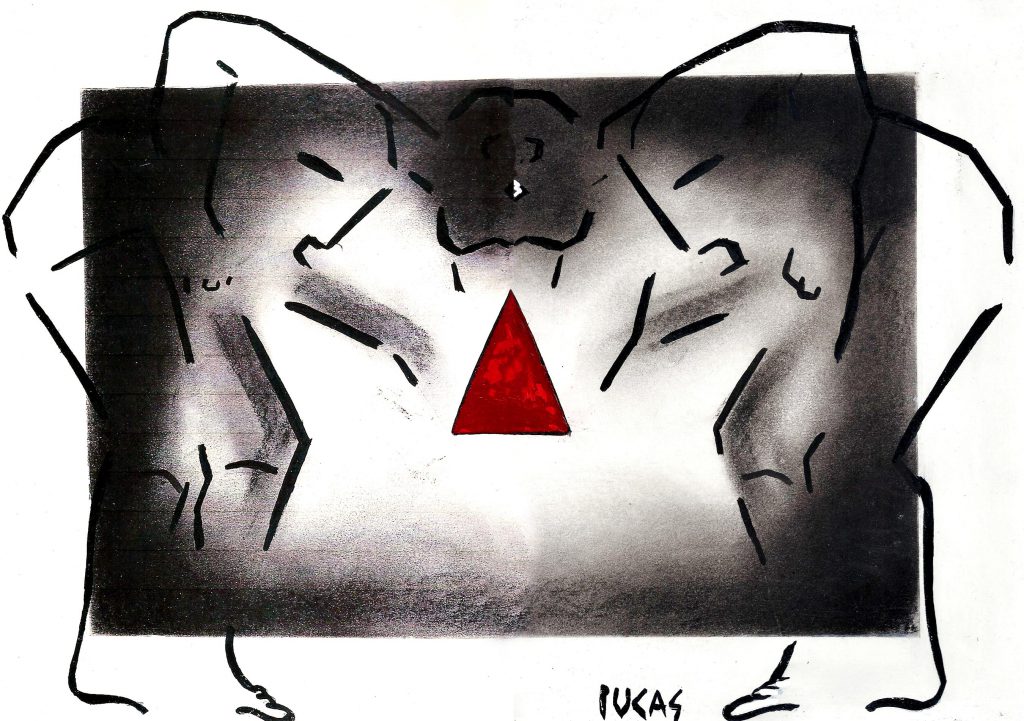

In a vaulted room, with sand for a floor, the artist hung three huge canvases on which he painted two symmetrical wrestlers: the paintings epitomise the fight by black people against injustice and lack of comprehension that have ruled the world since its inception. On each canvas he set aside a blank triangle that would be painted by Joseph N’Diaye, the House of Slaves’ custodian for forty years.

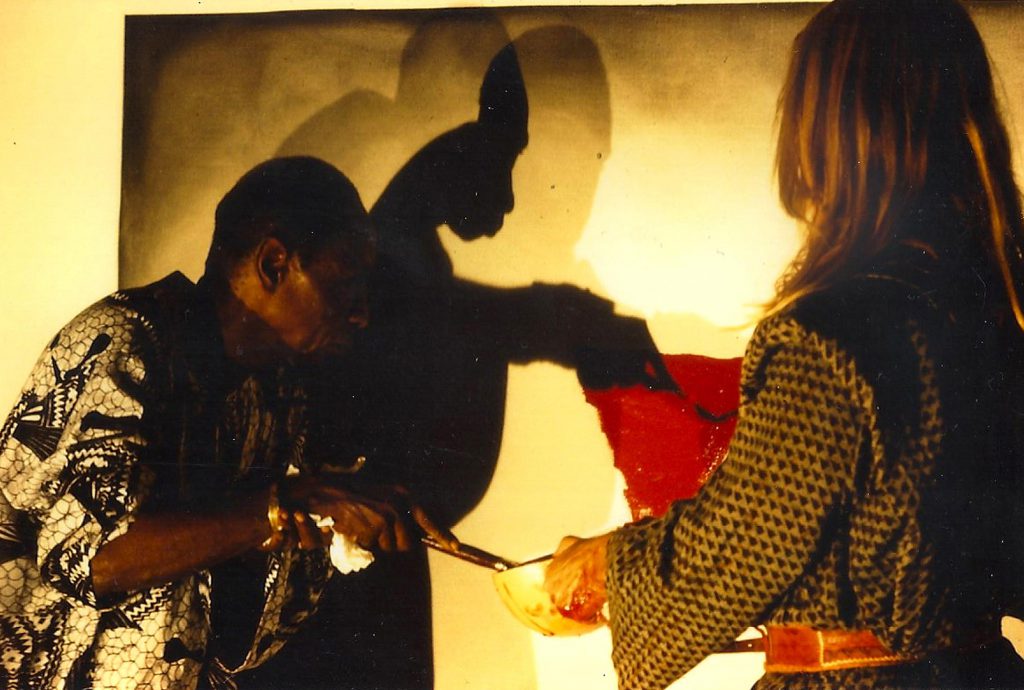

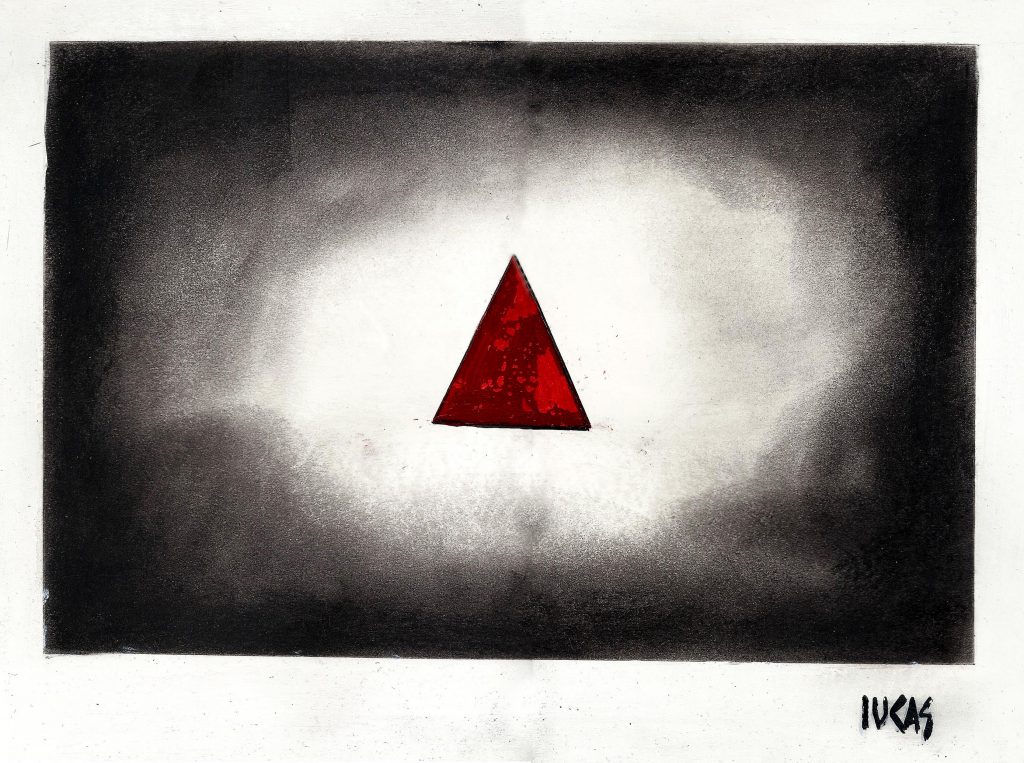

A living symbol of the incommunicability of human beings

LUCAS recalls: “Joseph, the last slave on African soil… Today, alongside him, I am the last white slave, the last free man. Like him, I am still shackled because both of us continue to dream of freedom… Joseph’s face conveys all the woes of this world. Apart from the odd, loud outburst when he explains the history of this House to a handful of visitors, the rest of the time his appearance is solemn and uncommunicative. He speaks softly as a mark of respect for the souls that rest here. Kneeling down, Joseph held out his wrist for me… This was to be a symbolic drop of blood… And then I hurt Joseph when I cut into the vein on his wrist, I hurt his body and his heart, and I hurt myself even more as if to exorcise the physical and moral suffering I had just inflicted on him. After a long while, still in a state of shock, Joseph painted this blank geometrical space. First he drew the outline – epitomising his life – then he began to fill it. At that point, it was no longer his hand but the spiritual projection of the invisible occupants of the House of Slaves, the tool with which they were vicariously engraving the history of a people, its suffering, its revolt but also its dreams of freedom on the canvas. This red triangle is the repository of their woes but also their hopes and their dream of freedom.”

Gorée will undoubtedly remain one of the vital links in the artists’ work where one can sense deep down the network of intimate connections and vibrant symbols of truth underpinning it. When we wrote that “Allowing men – in this case bullfighters who have transformed their life into a vocation – to take ownership of part of the canvas has opened up whole new graphic issues as well as new horizons for turn of the century art”, we could not have worded it better. Through this ritual celebration on a traditional painting medium, which shows great deference for its form and purpose, as René Huyghe said, LUCAS has given us a brilliant demonstration of the creative powers that are given to true artists.

Henry Périer, art critic and biographer of Pierre Restany, ‘the pope of New Realism’.

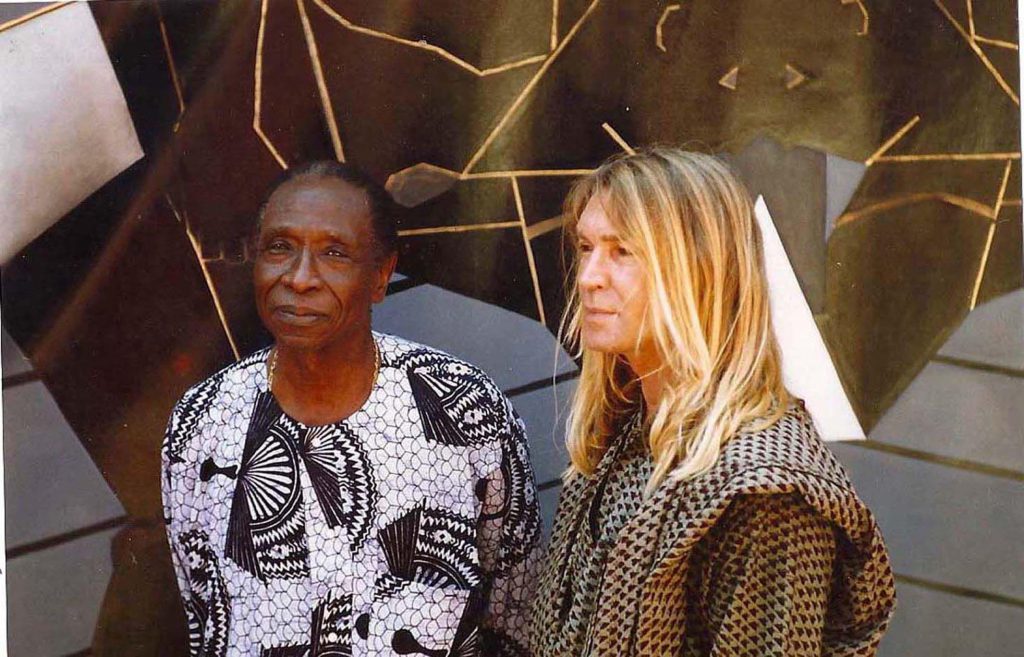

Island of Goree

Joseph N’diaye and Lucas in the House of Slaves

From my dreams, I was already familiar with the tiny Gorée Island in the Atlantic Ocean off Dakar. There was Joseph N’diaye whom I did not yet know, the last symbolic slave of Africa. When I met him at the House of Slaves, I told him what I had done with the bullfighters. I asked him to do a series of paintings with me so that he would be a part of a red triangle on the canvas. Africa, Dakar and Gorée Island are a far cry from the world of bullfighting but Joseph N’diaye felt that these men, the bullfighters, were extraordinary human beings that he would have liked to know…

His reply was instant. I will be waiting for you here tomorrow. With Joseph it was as if something was missing, his mind seemed to be elsewhere, in another era. Here, for centuries, men, women and children were shackled, branded with a red hot iron and sent to the Americas, not even as animals but as household objects. They were cooped up here in the House of Slaves, in the courtyard surrounded by high walls and in the cellars. For centuries they went along this corridor leading to the sea, dubbed “the door of no return”. Loaded onto galleys, the weakest, the sick, were thrown into the sea where they became fodder for the sharks.

In a low, dark room in the cellar of the House of Slaves, daylight filters through a kind of arrow slit. On the flaking walls, I set up the paintings produced for this ritual celebration, perpetuating ancestral rites whose profound meaning has travelled through the centuries from the dawn of humanity but of which we have ceased to be aware.

On each painting, I have left a geometric blank space which will become the soul of the pictorial composition. Joseph N’diaye will paint this blank part of the canvas with his blood mixed with red paint.

Kneeling down, Joseph held out his wrist to me. It was to be a symbolic drop of blood… and then I hurt Joseph when I tore the vein in his wrist, hurting his body and his heart, and I hurt myself even more, as if to exorcise the physical and moral suffering I had just inflicted on him.

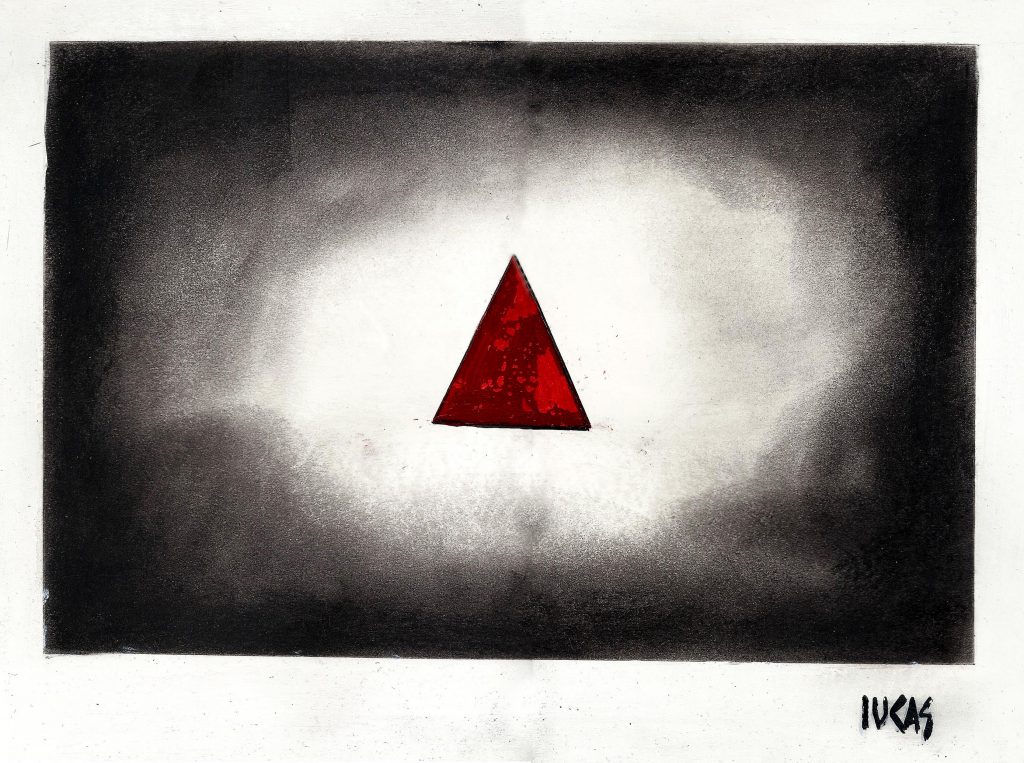

After a long while, Joseph – still in shock – painted this red triangle. He first painted the outline; that was his life he was depicting, before starting to fill in the rest. At that moment, this was no longer his hand, it was the spiritual extension of the invisible inhabitants of the House of Slaves, the instrument with which they wrote vicariously the history of a people, its sufferings, its rebellions, but also its dreams of freedom.

From the beginning of this ritual, Joseph and I were no longer there, time had stopped. Nothing of what surrounded us was perceptible to us anymore, we had crossed the boundary of reality, we were in another life, in another era.

This abstract red triangle painted by Joseph with his blood is the living symbol of man’s failure to understand, his destructive madness, irrespective of his colour, race or family.

A few hours after the end of this celebration, ideas, elusive and inexplicable impressions jostled in my head to the extent that they created a state of shock and indescribable uneasiness. For me, God willing, one day I will know why. The canvas carries the trace of the mystery, the evidence that it happened.

For 40 years I had been walking forward, putting one foot in front of the other, as Joseph N’diaye had done for much longer. What divine hand guided my steps to him, beset by my fears and doubts, but also lifted by my dreams and hopes? What mysterious force drove this wise man to accept this ritual with a human being he did not even know existed?

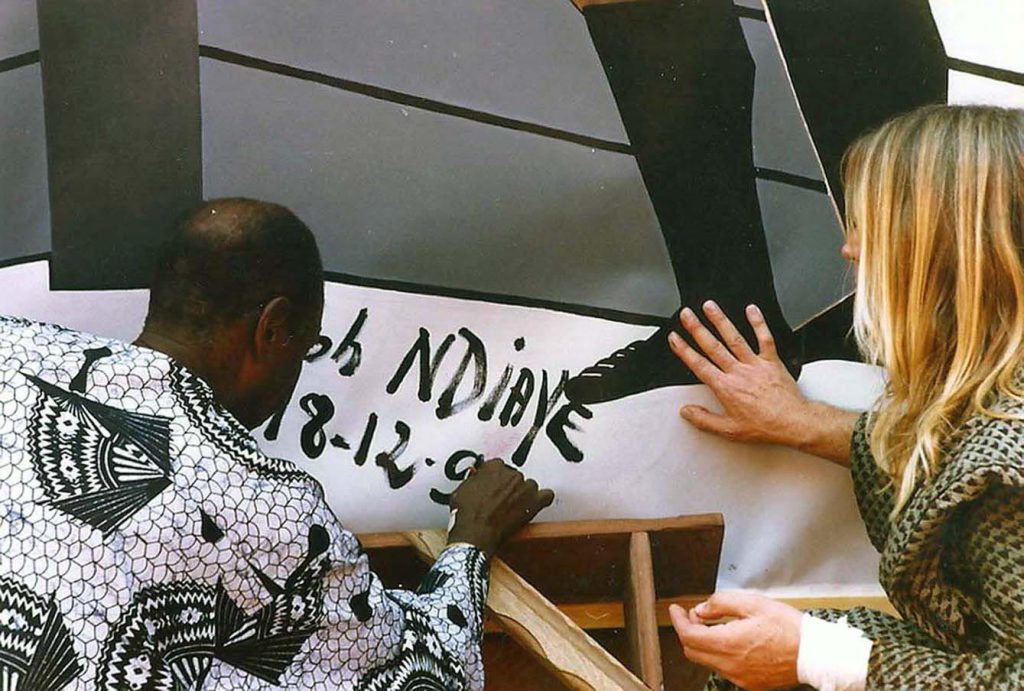

What mysterious force also pushed me to perform these primitive rituals, to hurt Joseph, his body, his soul, and to share pain with him? Does Joseph know this? Joseph and I met on December 18, 1992 and the steps we took individually from the beginning of our lives, other lives, brought us to this moment without warning. I will often think of Joseph. I will not be able to forget him because the mark of a mysterious, indescribable moment is etched on my wrist, like the mark he left on the canvas. The visual representation is abstract, the fundamental message can only be seen with the heart.

Joseph painted with his blood and mine mixed with red paint in a calabash.

With our DNA on the canvas, a part of our heart and soul will remain for aeons.

The last paradise on earth

I am an individualist. I have never been a militant, neither in action nor in thought for any cause whatsoever. My cause is People, with no distinction of race or colour. I did not perform this primitive, spiritual ritual to defend black people. They don’t need me.

Nor is it about symbolically connecting a black man and a white man, ostensibly showing that men are equal: they are not. They never have been. But the issue is not about race or skin colour.

Through this ritualistic celebration, maybe I went to meet Joseph, the last black ‘slave’ and worthy representative of the men who suffered here, in order to identify with them, so that Joseph would agree to let me share their chains, a symbol of misery, but also the dream of freedom.

The new slaves who have been robbed even of their dream of freedom are now part of our society, they live on our continents and are increasing in number and headed towards an irreversible process. In fifty years, a century at the latest, these black men of African soil will be the last ‘human beings’ on our planet, and the soil of Africa will be the last paradise. With this ritual, through and thanks to Joseph, perhaps I wanted to join them and thus free myself from my affiliation with these future slaves, these very next ‘inhuman beings’, due to my colour. With this ritual, I wanted to join those who will be the last free men. So this red mark, etched by Joseph N’diaye on the canvas, takes on extra meaning. It is a projection into the future of the symbol of freedom, the symbol of the last “human beings” on earth.