LUCAS or the signature of life

By presenting a complete set of 150 paintings by LUCAS, including 30 large format canvases (220×250), the Veranneman foundation offered the artist a spectacular introduction to the art world. In the heart of this prestigious venue and international centre for art, which serves as a focal point for contemporary schools of thought, the artist showed how extreme he could be. Reluctant to show his work, he had always stubbornly refused to exhibit. With the exception of a clutch of proponents of Outsider Art, his attitude was certainly not commonplace. Recognition by collectors was all he sought. LUCAS was waiting for his ‘opus magnum’. So when he joined the ranks of the select few, it didn’t go unnoticed.

Henry Périer, commissaire de l’exposition.

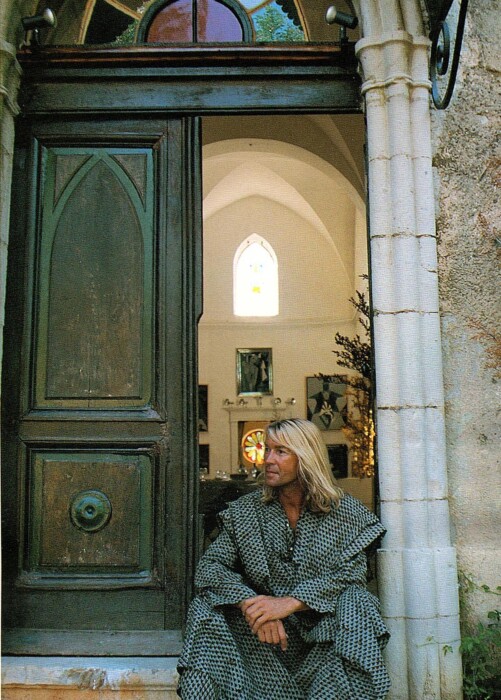

It was spring 1987. Having returned from St Tropez, where intellectual enlightenment plays second fiddle to the shallowness of appearances, Lucas confided in me of his ‘idea’. A few months earlier, I had already been the privileged witness of an event that occurred in the chapel where he worked. In this extraordinary place, located just a stone’s throw from the most ancient prehistoric village listed in France – Cambous – Lucas had invited me to come and discover his latest painting, executed in walnut stain on the nave wall and featuring a horse and a man.

The shape of the drawing, the materials used and the backdrop of brown sand were reminiscent of the paintings found in prehistoric caves. The artist pointed to a rectangle he had drawn at the bottom of the wall.

“You see, if I were to pass away, there will be a lasting memory of me here forever!” We ventured no further. Little did I imagine the kind of adventure I would be drawn into…

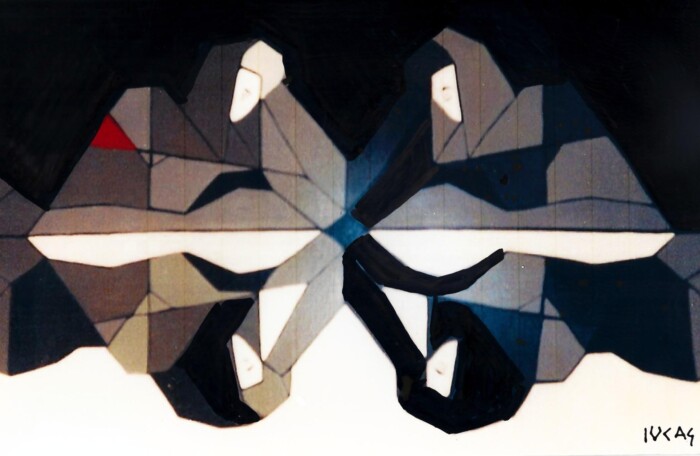

September 1989. The man from Sanlucar de Barrameda, from the marshlands of the Guadalquivir, and legend of 1980s Spain, was standing in front of us. He had come solitary and alone. The huge paintings arranged on easels formed a vast fresco dedicated to bullfighting. The atmosphere was electric. The solemn-faced bullfighter, his cheeks marked by deep furrows. The aloof and extremely tense artist. And so the ritual began. Paco Ojeda concentrated whilst he filled the geometrical spaces that Lucas had reserved for him on his canvasses. The chief operator, the cameraman and the sound engineer stood with baited breath, daring only to communicate using gestures. The scene was strange. It was an indescribable, religious moment.

The man who, in the bull ring, stands straight, riveted to the ground and motionless as he slides his cap over the bull’s horns for minutes that seem to stretch into hours, made a symbolic gesture in the chapel, fully grasping its significance. Before us, he became an integral part of the artist’s work, in what was a surreal and unique moment.

These magical moments of intense emotion would be replicated with Juan Antonio Ruiz ‘Espartaco’, José Ortega Cano, Miguel Baez ‘Litri’, Juan Mora and Richard Millian.

How could Lucas know this? How did he discover, through pure intuition, that this gesture had been made by the very first human beings? Some are convinced that Paco Ojeda’s hypnotic power over animals is a legacy from his previous lives when he himself was a bull! This begs the question: was the artist in the caves of Lascaux 10,000 years ago?

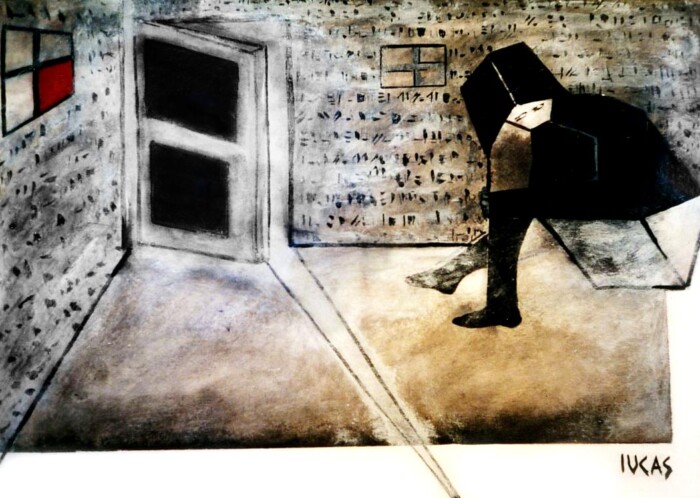

Whatever the truth, Lucas learnt to become an artist in the studio of Jean Denys Maillard, the portrait artist of kings and the celebrities of this world. The gift that allows him to capture the physical resemblances and psychological truths of his subjects was able to thrive in an atmosphere that was closer to the great traditional art forms than to contemporary art. Gradually, however, he would break away from this type of art to assert his personality and vision of the world. He would adhere to a different set of ascetics, creating a world where he would forget the colours of his first artistic period. For years, he would work with the different shades of blue with greater austerity, rigour and intensity.

In 1986, he added a patch of red to his paintings. What may have seemed at the time like an artificial gesture aimed at visual impact would in fact turn out to be a premonition. Lucas was developing a whole new language.

Having stubbornly refused to exhibit until now – he was waiting for his ‘opus magnum’ – he provides us with a complete and extensive collection of artwork at the Fondation Veranneman in Belgium which combines his artistic journey and real-life experience.

Allowing men – in this case bullfighters who have transformed their life into a vocation – to take ownership of part of the canvass has opened up whole new graphic issues as well as new horizons for turn of the century art.

Henri Perrier

Exhibition curator

“… In 1986, he added a patch of red to his paintings. What may have seemed at the time like an artificial gesture aimed at visual impact would in fact turn out to be a premonition. Lucas was developing a whole new language…”

Henry Périer

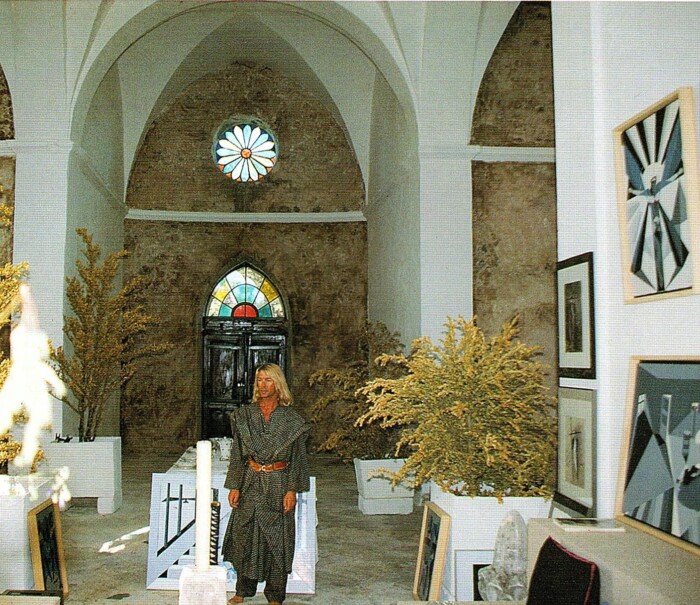

Lucas in front of his chapel at Château de Cambous

In the darkness surrounding me until now, a dot shines on the horizon and the path leading to it already lights up my life. Sometimes, I even think it is divine intervention because, after all, this strange idea came to me in the chapel where I live and work.

And the wounded bird I took in was the same colour as the stained glass windows when sunlight shines through them.

The bird has flown off in search of its distant country, but did it leave me this message? Whose divine hand put it across my path?

Life is full of enigma – what seems obscure today becomes clear tomorrow and, God willing, one day I will know why.

The entire composition of my paintings is dictated by geometrical shapes. On each painting, I will leave a blank space – a square, triangle or other geometrical shape – to mark the vital and focal point of the painting.

I will ask exceptional people to paint on this blank space with ‘blood’ and write their name next to mine.

What captivates and enthrals me about this idea is that for the first time, someone other than the artist will play as significant a part in the creative process, adding the final touch without which the canvas would remain incomplete. In art, the idea and philosophical discourse surrounding the idea count as much as the work of art itself.

This tiny painted part of the canvas will form the heart and soul of the painting. It will also stand out from the main composition to become a work of art in its own right.